Is METR Underestimating LLM Time Horizons

TL;DR

Using METR human-baseline data, I define an alternate LLM time-horizon measure, i.e. the longest time horizon over which an LLM exceeds human baseline reliability (or equivalently the intersection point of the human and LLM logistic curves), and this measure shows a much faster growth-trend than METR’s fixed-threshold trends: doubling every 1.9 months, versus 6.8 months for the 50% METR-trend over the same time period. Also, since this metric is directly comparing to human baseline reliabilities (unlike the METR fixed-reliability estimates), we can use it in a more principled way to assess time to human-level horizons, which suggests roughly 2026-2027, with substantial uncertainty.

METR has generally deemphasized their human reliability baselines, on the grounds that the participants were poorly incentivized to complete long tasks; however, this post argues that comparing to this imperfect human data is likely a better reflection of progress towards human-level agency than the current METR horizon trends that use fixed reliability targets even as task length increases.

AI-2027 has argued controversially that the METR trends may actually be more accurately modeled as super-exponential, with finite-time blowup; this post argues that while this claim does not seem to be very well supported (yet) for METR’s time horizon measure, this super-exponential model is more strongly supported for the proposed human-relative time horizon metric described in this post.

See addendum at the end for an update regarding the recent Claude Opus 4.5 METR results.

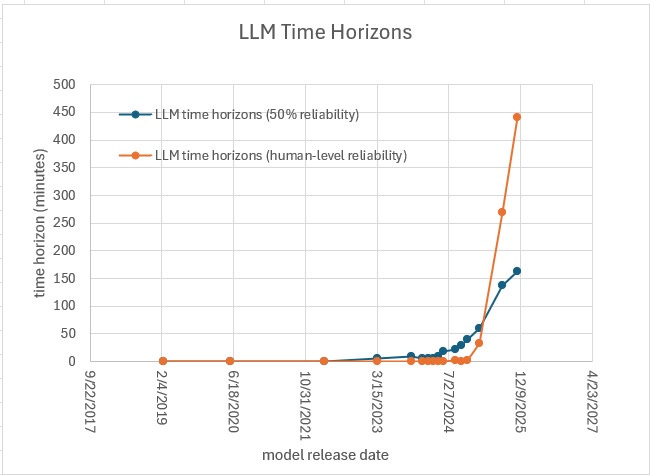

Figure 1: Plot comparing frontier LLM time-horizon measures, including both the human-level-reliability time-horizon from this post (orange), versus the METR-style fixed-reliability 50% time-horizons (blue). We can see that this alternative human-relative time horizon measure has been increasing much more steeply over time than the METR horizons. Note that the “human-level” horizon metric in this plot is comparing LLMs to METR’s human baselines. The most recent data point included here is gpt-5.1-codex-max.

Acknowledgements: I shared a draft of these ideas last year in correspondence with Daniel Kokotajlo and Eli Lifland from AI Futures. Thanks to Eli for his feedback; also, Daniel subsequently posted a short-form [1] touching on a similar crossover/intersection point framing, which is worth checking out for his perspective on these issues.

1 Summary

The METR time-horizon metric provides estimates for the longest software tasks that a given AI is capable of completing [2]. This estimate is based on human baseline measurements for how long a set of software tasks took human engineers, with the (geometric) average time based on the subset of humans who succeeded at each task. METR also measured human reliability at each task, but rather than compare the AIs to those human levels, they have typically reported LLM time horizons at fixed reliabilities independent of task length (e.g. 50% or 80%). The METR estimates have featured prominently in efforts to estimate the timeline to human level long-horizon agency, e.g. per the AI-2027 forecasts[3]. The following bullets describe potential downsides of this METR horizon approach and summarize the proposed alternative, as well as providing trend-based projections for these metrics.

1.1 Potential Downsides of the METR Metric

Lack of human comparison: If the goal is to assess progress towards human level horizons, what we should ideally be doing is not comparing to fixed target reliabilities at each horizon length (e.g. METR’s 50% and 80% targets), but rather comparing to baseline human reliabilities at each horizon. Note that both METR and others (e.g. AI-2027[3] or Greenblatt[4]) routinely use these fixed-reliability horizons to track progress towards human-level horizons, which perhaps feels like a natural assumption since the horizons were human-derived, but the problem is that the fixed reliability targets (even as difficulty/duration increase) are not based on any actual human baseline performance.

Unknown difficulty trend complicates interpretation: METR relies on fixed reliability (e.g. 50%) trends to predict LLM time horizons compared to humans, but there is little reason to think that humans can achieve 50% reliability for long tasks of arbitrary difficulty, e.g. for tasks along the unknown METR task-difficulty trend. Many people have the intuition that humans can handle tasks of arbitrary length at high reliability, but of course that depends on task difficulty, and while we can extrapolate the METR curve to weeks or months, the existing/actual tasks are short, so it’s not clear how to estimate the difficulty of hypothetical long METR tasks. There is a tendency to assume these would just be typical long software engineering tasks (e.g. merely time-consuming due to many fairly straightforward subtasks), but there is not much basis for that assumption, as opposed to longer tasks on this length/difficulty trend being more like “prove this tricky mathematical theorem”, etc; in other words, there are multiple dimensions that are getting compressed into this task duration factor, including “repetitiveness” and subtask count, but also “intrinsic difficulty”, etc, and the intuition that humans can handle long tasks at high reliability only really applies to the former. Note that if METR adds new longer tasks to their benchmark, they can of course make them as easy or hard as they want, but when they extrapolate their existing time-horizons to longer task lengths, the long task “difficulty” is implicit in the trend and not something they get to choose.

Potentially unattainable bar for human-level: A related issue is that if we require AI to exceed a fixed 50% horizon at every time horizon in order to be considered human level, then it’s not clear that this will ever occur, since for both humans and LLMs reliability tends to decrease with horizon length and difficulty (see more detailed discussion in the formula section below); by contrast, with the alternative metric that compares to actual human-level reliability at each horizon length, there is no barrier in principle to AI surpassing humans at every time horizon. A related issue is that when projecting the existing METR metric to “human level” it is really unclear what horizon constitutes human level since the fixed reliability metrics aren’t grounded in human reliability measures, e.g. see the wide range of targets for this in the AI-2027 forecast[3], whereas with this human-relative metric it’s straightforward that human-level requires matching/exceeding human reliability at every task duration, per the projections below.

Underestimated horizon lengths: The time horizons for METR are based only on the humans who actually succeeded at the tasks, so if you allowed all the humans more time to finish, the lower performing humans would presumably take even longer; so the current METR horizon lengths are likely an underestimate relative to METR’s average baseline engineers; note the estimates are also properly interpreted as an average over METR’s top baseline engineers, since it sounds like different engineers succeeded at different tasks. These underestimated horizons potentially create bias that could make the LLMs appear to have worse horizons than they really do. However, the proposed human-relative metric does not address this particular downside, since it reuses the METR horizon lengths.

1.2 Alternative Human-Relative Metric:

As an alternative to the fixed-reliability (e.g. 50%) METR time horizons, we can instead measure a time horizon metric that is defined relative to actual human baseline reliabilities; note that METR did actually measure human baseline reliabilities, though they tend to down-play those baselines as weak or insufficiently incentivized (see section 1.6 below) and instead focus on absolute reliability targets. One issue is that current LLMs e.g. gpt-5 already exceed the METR human baseline time horizons at both the 50% and 80% targets; however, humans do still have fatter tailed reliability curves, so for longer tasks METR’s human baselines still do better (though see Addendum below on Claude 4.5, since this claim is less clear now). For instance, gpt-5 has worse reliability than the human baselines once the METR task length gets longer than 4.5 hr, but note its 50% horizon is only 2.3 hr. Using these human-reliability baselines, we can estimate LLM time horizons, as the longest task duration over which the LLM is more reliable than the METR human baselines, or more concretely, as the intersection point of METR’s logistic fits for humans and LLMs, with a fit of reliability versus task duration. See Figure 1 for a plot comparing these two horizon metrics over time.

1.3 Trends in Human-Relative Metric (exponential fit)

The trend in this human-relative time horizon metric is increasing much faster than the existing METR trends, and assuming an exponential fit, the LLM time horizons at human-reliability are doubling every 1.9 months, versus every 7 months over the same time period for the METR (50%-reliability) time horizon trend (see Table 1 and Figure 2). In other words, every 1.9 months there is a doubling in the longest time horizon that LLMs can handle at METR’s human baseline reliability. As METR has noted this exponential appears to have sped up recently, perhaps since the arrival of reasoning models, though the estimates above are just using all of the data for both metrics (not just the recent models); however, the hyperbolic analysis below does implicitly model increasing exponential rates over time.

1.4 Evidence for Super-Exponential (hyperbolic fit):

Theoretical reasons to expect hyperbolic trend: For the human-reliability-based trend, LLMs are linearly improving their logistic slope parameter over time (though the trend is noisy) so if this linear trend continues and this slope catches up the human slope, then the time horizon would jump to infinity as the LLM exceeds human reliability at all horizons (the logistic intercept parameter is already better than human and steadily increasing). Note that people sometimes assume there is something unrealistic about blowups to infinity, but while that can be an issue for physical quantities, it is not a concern for abstract metrics like “the set of horizons where LLMs exceed humans”. And this finite-time blowup can be naturally modeled with a super-exponential (hyperbolic) trend, whereas with an exponential fit, the LLM would never exceed humans over all time horizons; note that this argument supporting a hyperbolic fit does not directly apply to METR’s (fixed-reliability) horizon metrics, since even humans typically have declining reliability with difficulty/task-length, so matching human slope (and intercept) would not lead to a blowup in METR’s metric (See Addendum below on Claude 4.5, which has effectively caught up with the human slope, at least per the weak METR human-baseline)

Statistical evidence for a hyperbolic fit: Based on AIC-model selection (see Table 3) the human-relative time-horizon trend appears to be closer to hyperbolic than exponential, whereas the METR horizon trends are a better fit for an exponential trend, though more data is likely needed to say this conclusively (See Addendum on Claude 4.5).

AI-2027 super-exponential projection: The AI-2027 project has argued, with some controversy, for using a super-exponential finite-time blowup for projecting the METR fixed-reliability (80%) time horizons; per above, this seems poorly supported in that fixed reliability case, but it is much better supported for this alternative human-relative horizon metric. So my sense is that their core super-exponential time horizon intuition may turn out to be correct once you make this adjustment to the metric.

1.5 Projections to Reach Human Level (hyperbolic fit)

Per above, with an exponential fit, LLMs would never catch up with humans, but with a hyperbolic fit the current trend suggests human level by around mid 2026, relative to the (weak) METR human baselines (see Table 2). That table also shows sensitivity analysis with hypothetical stronger human baselines, with the two alternative baselines pushing human level into 2027. These stronger baselines have flatter slope, with human reliability dropping more slowly with longer horizons, but they still do gradually decline, in contrast to the METR horizons based on constant reliability targets.

1.6. Downsides of the Proposed Metric

METR has generally minimized the relevance of their human reliability baselines on the grounds that the participants weren’t properly incentivized, and these weak baselines are a potential downside for this proposed metric; but in so far as we are trying to determine LLM progress towards human-level agency, then we are likely better off comparing to the available human baselines (even if imperfect) rather than absolute reliability thresholds that have no known connection to actual human performance; for instance, based on METR’s human-baseline logistic fit, we should expect humans to get about 3% reliability for tasks at 1-month horizon (along the METR difficulty trend line), so it’s not clear why we would require “human-level” AI to get 50% (or 80%). That said, in so far as the human baselines are weak or poorly incentivized, it could be useful to collect stronger human baselines, or for now we can do sensitivity analysis with hypothetical stronger baselines (see below) to assess how much this changes projections.

Continue reading the full analysis